The study is a tour-de-force of research and history by Andrew and Richard, and I’m very grateful to have been invited in to assist with the accounting and systemic analysis of the structures that lie at the heart of the UK monetary system and add my little bit to the document. However I do stand on the shoulders of giants.

The study proves conclusively that the source of ‘moneyness’ in the UK is the Consolidated Fund, and that the whole of the Sterling currency area derives from its activities - to the extent that we can show that the ‘net financial wealth’ of the non-government sector that arises from the MMT viewpoint is precisely balanced by a ‘sui generis’ asset that sits on the balance sheet of the Consolidated Fund. A balance sheet that is never fully drawn up anywhere.

The Bank of England is just a bank and operates in the same manner as any other bank (to the extent that it requires capital injections from HM Treasury to maintain its loss adjusting buffers). A bank that is and remains, both legally and structurally, subsidiary and subservient to HM Treasury in all ways. Its primary task is to discount liabilities imposed upon it by HM Treasury into bank liabilities. It does that by order of HM Treasury, has done since at least the 19th century, and continues to do so today. The Bank has no legal authority to refuse those orders.

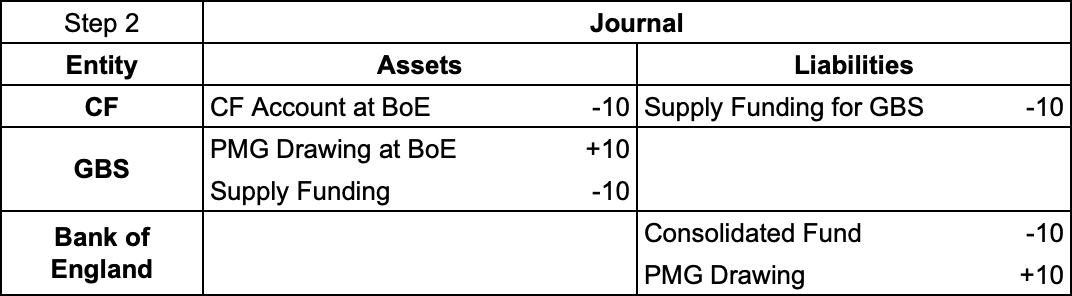

On a morning the Consolidated Fund account at the Bank of England starts with a zero balance. The first order of business is to authorise and transfer sufficient funds from the Consolidated Fund Account to the Paymaster General Drawing Account(s) ready to clear BACS payments initiated three days earlier. The journal for that looks like this

Within the Government Banking Service, the internal bank within the Exchequer, a mirror transaction occurs moving the same amount of money from the Supply funding account to the record of the Drawing Account within GBS. The Supply Funding account is the source of Parliamentary funds and that matching transaction is what transforms ‘Exchequer Credits’ into ‘Sterling’ - by force of law.

Government has a special BACS grade designed just for government payments (BACS Grade 3, or government grade - as distinct from the other two ‘Consumer grade’ and ‘Bank grade’). This allows the HM Treasury to use a different account at the Bank of England as the source of payment, as distinct from the account where the debit will be applied. That ‘Nostro’ account is the Paymaster General Drawing Account. (Nostro/Vostro processes are ancient banking mechanisms arising in Italy during the Renaissance).

The result is that the Consolidated Fund account at the Bank of England is debited and the Drawing account is credited with whatever amount is required and the BACS transfer takes place - using the Drawing account to pay everybody that is scheduled to be paid by the government today.

The Consolidated Fund runs an intra-day overdraft which is offset by other accounts held by HM Treasury.

So what is the offsetting account? This is the job of the Debt Management Account (DMA) run by the Debt Management Office (DMO). The task of the DMO is to drain money from the banking system to offset the injections that are coming from the rest of HM Treasury. And it does this by exchanging gilts and Treasury bills for the excess money HM Treasury is constantly adding to the bank system.

This process runs alongside the payment system in real time and is coordinated by cash flow reports from the rest of HM Treasury to the DMO several times a day. DMO tries very hard not to disrupt the money markets with its activities, while at the same time aiming to offset HM Treasury’s activity at a net cost that is less than the default alternative - which is just to leave the banking system with the extra money. The DMO explains the process in its annual review:

The DMA is used to manage the Exchequer’s net cash position. Balances in central government accounts contained within the Exchequer pyramid are swept on a daily basis into the NLF and the DMA is required to offset the resultant NLF balance through its borrowing and lending in the money markets. The DMA is held at the Bank of England and a positive end-of-day balance must be maintained at all times; it cannot be overdrawn. Automatic transfers from the government Ways and Means (II) account at the Bank of England would offset any negative end-of-day balances, though it is an objective to minimise such transfers.

Although the DMO has a very good idea of what payments will be going out on a particular day, what it doesn’t know is how much tax will flow into HMRC’s general account at the Bank of England. That is very much the stuff of educated guesses.

Since this uncertainty may lead to the DMA becoming overdrawn, and it is a KPI of DMO to avoid that, the DMA maintains a variable positive balance overnight as a buffer against this cash flow forecast uncertainty.

So where does this buffer come from? Surely it is borrowed in the market? Well when you analyse the processes and net them off, as we have done in the study, you find that it is an identical mechanism to a capital injection by HM Treasury. It is entirely illusionary. There to make the numbers look good and allow a net movement around ~+£1bn rather than zero. The non-government sector actually has no less money overall.

Updated 20-Feb-2021 to include the Government Banking Service