Summary

In 2012, the Bank of England agreed to transfer gilt coupon payments received within the Asset Purchase Facility to HM Treasury. That resulted in a “positive cash flow” from the Bank to HM Treasury of some £120 billion over the period since then. However, this becomes net zero when viewed from a “whole of government” perspective since the coupons came from the Consolidated Fund in the first place.

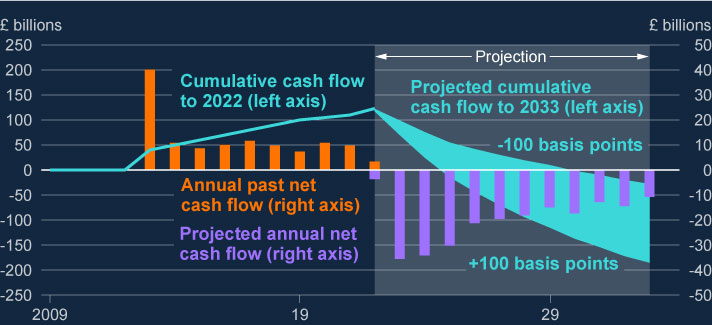

Now the Bank of England has decided to sell the gilts in the Asset Purchase Facility as part of its unwinding programme, which has already resulted in an emergency transfer payment from HM Treasury to the Asset Purchase Facility using the Contingencies Fund. Further transfers are expected to total some £80 billion or so over the lifetime of this Parliament.

Under the current approach, payments will require voted funding from Parliament and will cause more gilts to be issued by the Debt Management Office. This will increase the amount of debt interest due to banks, increase government spending, and interfere with the Bank of England’s monetary policy.

This paper lays out an alternative using existing resources and legislation that requires no further vote funding in Parliament, no additional debt interest payments, and likely restores the “positive cash flow” of the Asset Purchase Facility for the remainder of this Parliament.

The procedure is simple and is as follows:

- Transfer the ~£90 billion of assets in the Issue department of the Bank of the England to the Banking department and write them off against the Asset Purchase Facility Loan.

- Revalue the assets of the Issue department under section 9(2) of the National Loans Act 1968.

- The Issue department then receives a ~£90 billion asset from the National Loans Fund under s9(4) that is interest free due to section 9(4)(b).

- This asset should be held as a deposit in National Savings by the Issue department. In the future, when banks buy notes from the Issue department, the proceeds are deposited in National Savings, automatically increasing the size of the section 9(4) asset.

The result is ~£90 billion of headroom in the Asset Purchase Facility to allow the unwinding to proceed without further involvement from Treasury.

The rest of this paper explains the details.

The Problem

Quantitative easing (QE) has a fundamental issue. It buys gilts when the price is high and sells them back when the price is low. This loss in value is supposed to be absorbed by holders in the private sector. It’s one of the mechanisms by which monetary policy is supposed to work - making fixed-income holders feel poorer by altering their portfolio value (even though the redemption return remains the same).

With QE in place that won’t happen for the assets that have been replaced. The private sector has the money, and the Bank of England holds the gilts. When interest rates rise the private sector banks get more money in the form of additional interest on reserves but their asset values stay the same. Instead, the notional loss shows up in the government sector - exacerbated by the decision to sell gilts within the Asset Purchase Facility at a loss rather than holding them to redemption or have HM Treasury redeem them early under s14(6) of the National Loans Act 1968.

The result is that the Asset Purchase Facility, where the gilts are held, will have a notional negative cash flow of some £30 to £40 billion per year to be settled by HM Treasury.

The Standard Solution

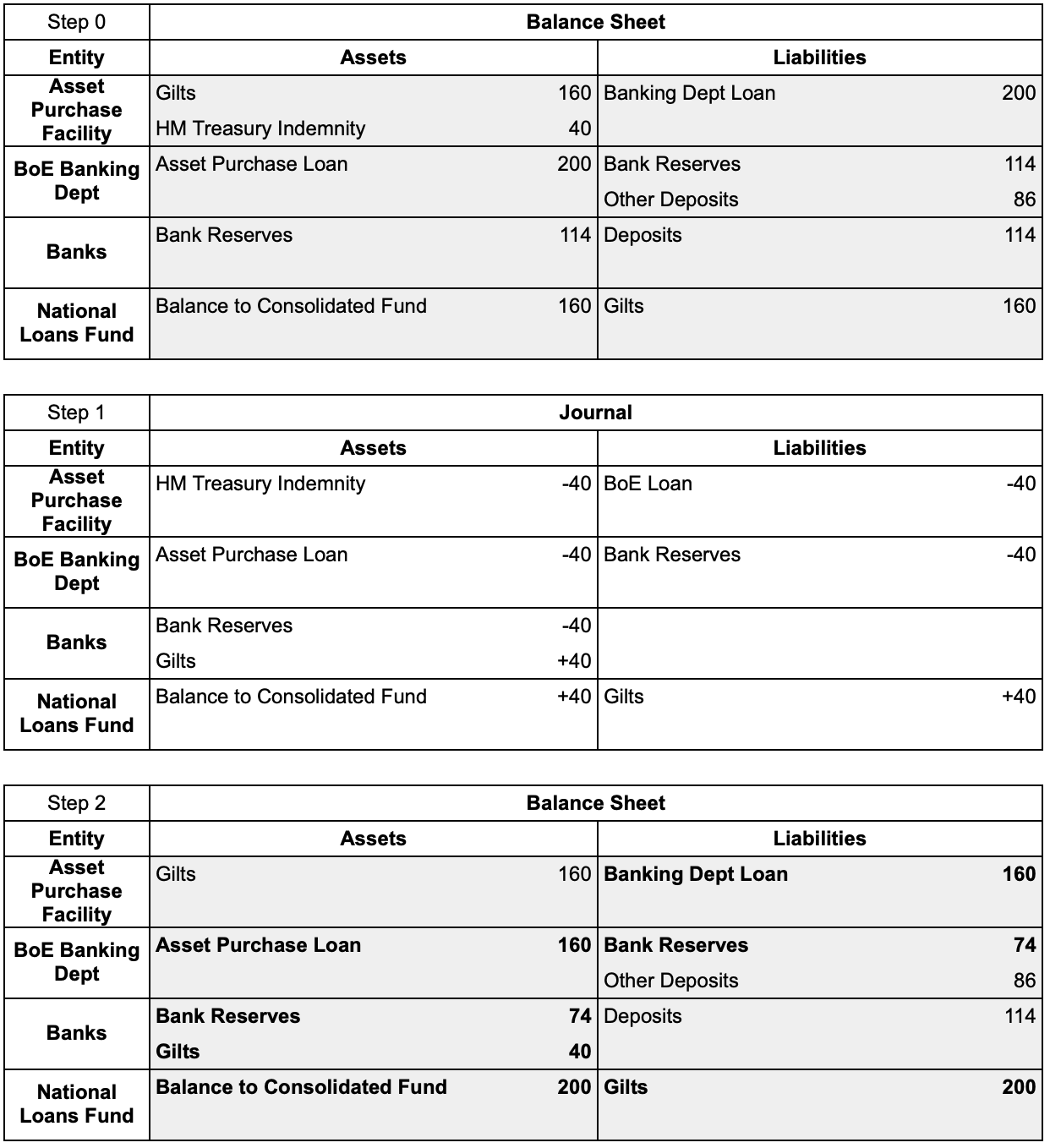

The indemnity will be settled by HM Treasury transferring £40 billion to the Asset Purchase Facility which will then use it to reduce the size of their Bank of England loan. This amount will be quoted in HM Treasury’s supply estimates and nodded through by Parliament in a Supply and Appropriation Act. It will add to the size of government spending and allow those who are hard of accounting and understanding to do their usual political point scoring.

However, in economic terms, the effect is straightforward. The Debt Management Office will sell £40 billion worth of gilts to banks as part of the daily cash management process. This will hoover up £40 billion of the ‘excess’ bank reserves already in the system. The effect will be the same as with the Bank of England’s sales - reserves at a low floating interest rate are removed and replaced with higher fixed interest rate bonds.

In cash terms it means banks get paid more interest from the government sector, which has to be paid every six months as an additional coupon adding further to the quantity of government spending.

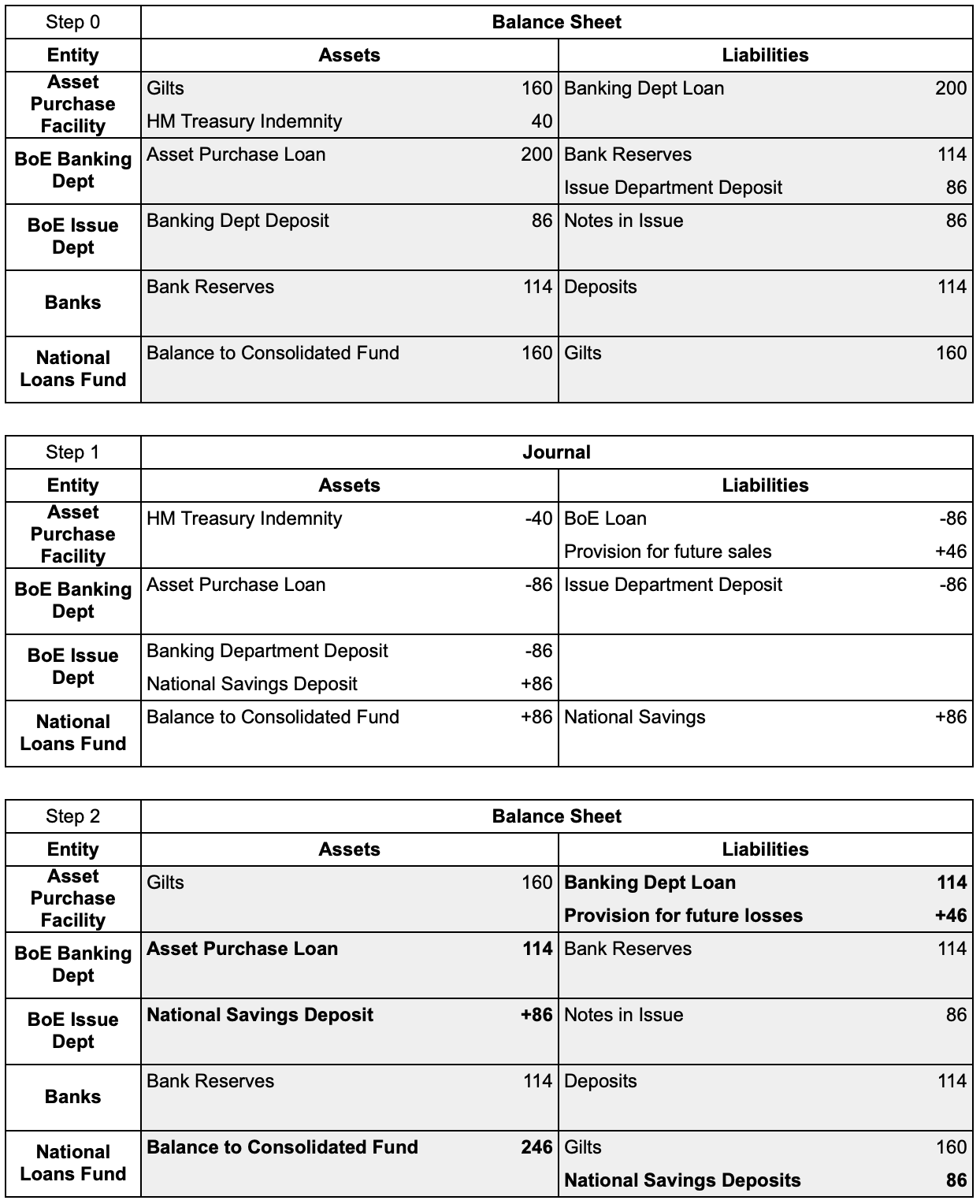

The accounting extract for this solution, for a current year negative cash flow of £40 billion, looks something like this.

The Alternative Solution

An institutional analysis of the situation presents an alternative solution that is costless to HM Treasury, in terms of vote funding and ongoing interest payments, and which avoids HM Treasury from interfering with the Bank of England’s current monetary policy remit.

Over the course of the last decade and a half, there has been another effect of the asset purchase policy that hasn’t, as far as I’m aware, been discussed anywhere else. There has been a marked increase in the Issue department’s deposit balance with the Banking department and a marked decrease in the quantity of HM Treasury assets it holds.

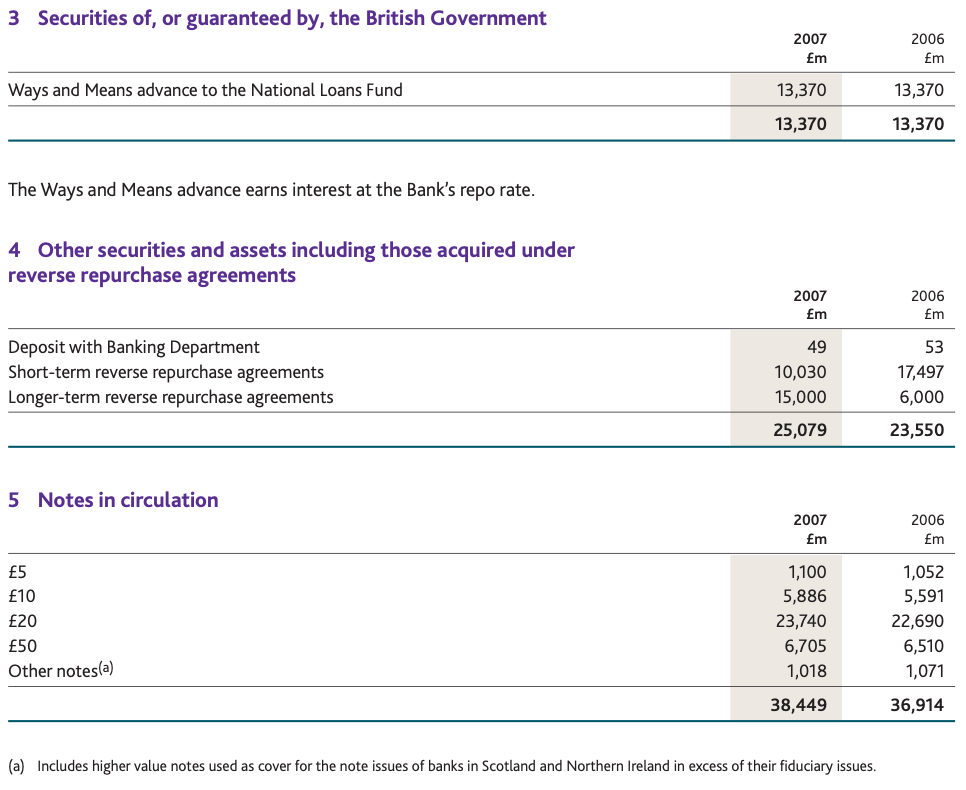

Here’s an extract from the Bank of England Issue department Accounts from 2007

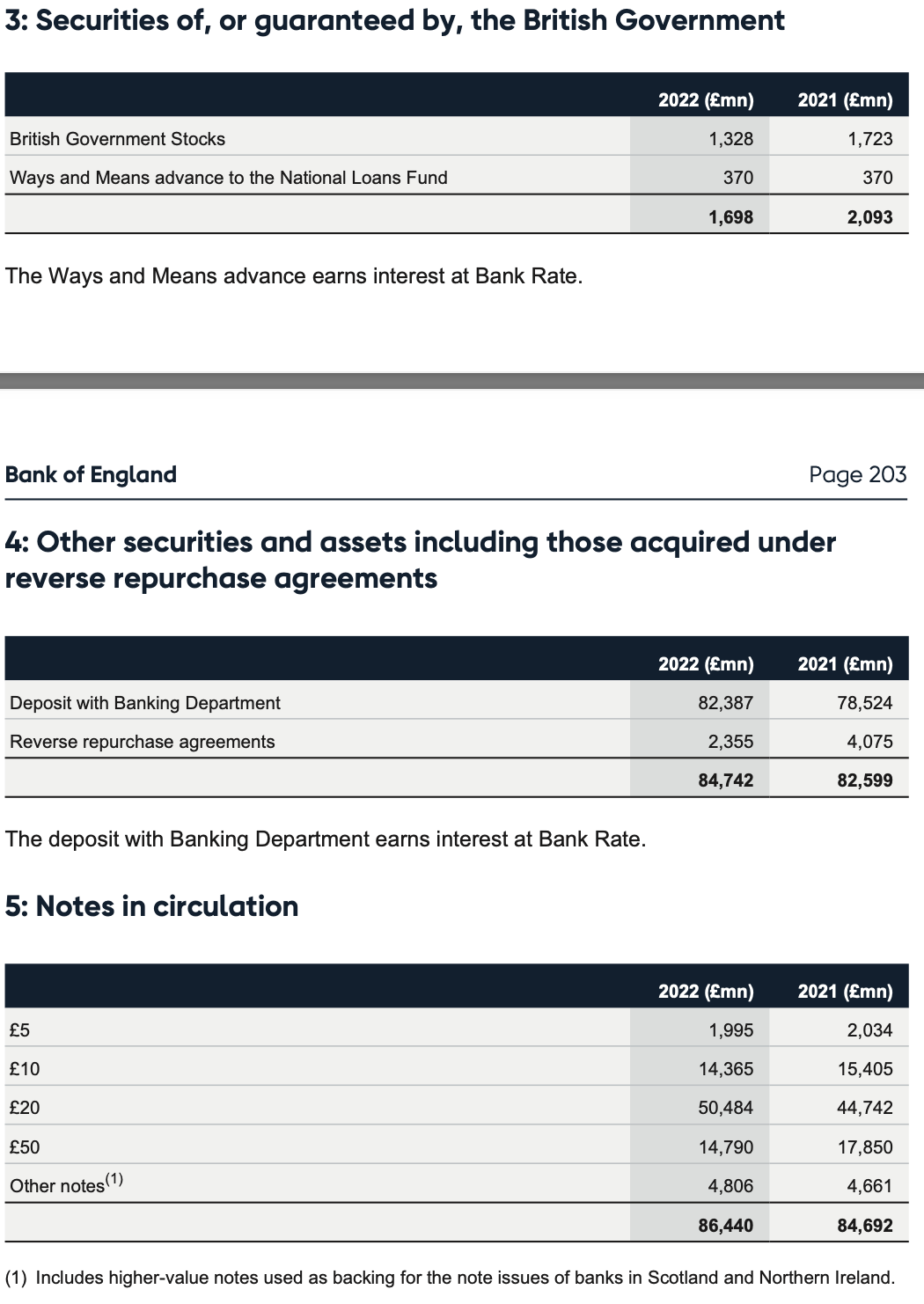

and the same extract from 2022

As you can see, the deposit with the Banking department has gone from £49 million to £82,387 million.

This increase is the solution to the Asset Purchase Facility problem. HM Treasury should direct the Bank of England to write off the Issue department’s assets against the Asset Purchase Facility loan. This is standard advice. There is no point in having savings if you have debt.

That would reduce the Asset Purchase Facility loan by at least £82 billion which is sufficient to cover the projected cash flow for the rest of the current Parliament.

All the assets could be transferred, they could be redeemed and then transferred (under s14A of the National Loans Act) or the transfer could be limited to just the existing Banking department deposit.1

Once the assets have been transferred, the Issue department should be revalued under s9 of the National Loans Act 1968.

This will result in a new s9(4) asset arising within the Issue department from the National Loans Fund, that is interest-free (thanks to s9(4)(b)), and which will back the notes in issue from then on.

HM Treasury should consider having this asset managed as a deposit in National Savings. This would allow the Issue department to deposit the income from any further sales of notes into their National Savings account - automatically extending the s9 asset. All via a simple bank transfer.

In addition, the intricate revaluation flows to and from the Issue department that we see within the National Loans Fund accounts are permanently eliminated. Future Issue Department balance sheets would become pleasingly simple and descriptive. The accounts are not only correct but look correct.

Notes in issue are indeed National Savings.

Eliminating needless transactions is a small efficiency gain but a welcome one.

Overall, headroom within the asset purchase facility is increased by at least £82bn, all without any further vote funding from Parliament, any further use of the Contingencies Fund and without incurring any additional debt interest payments now or in the future.

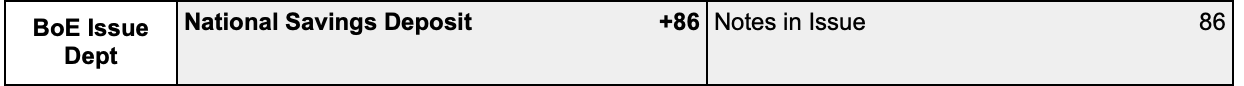

The accounting extract for this solution, assuming an s14A redemption route and the £40 billion current year negative cash flow as previously, looks something like this:

Chat about this and any other MMT topics on Discord with the growing New Wayland community . New members can click this invite link which will add the server to your Discord account

The current elaborate dance where the Banking department pays interest to the Issue department to cover note costs incurred on note production and management by the Banking department should be eliminated. Either the costs should be covered by HM Treasury as voted funding, or charged to the banks via the usual Bank of England cost-covering regulation fee. ↩︎